Men Aren't Lonely, We're Scared

We're broken, but we don't have to be.

Men are lonely. No, it’s not women’s fault. No, it’s not men’s fault.

But it IS men’s job to fix it.

Now that I’m in the thick of my 20s, there’s an air of impending doom to the male loneliness epidemic. In the years since COVID I’ve seen many friendships of mine shrivel up and die, often right before my eyes.

I grow increasingly nostalgic for the halcyon days of my freshman year in college, when my life felt like an endless sitcom- adventure around every corner, a new, wonderful place to explore, and an all-encompassing sense of community.

Then, of course, you all grow older, your careers take shape, you’ve got work in the morning, and soon you realize you’ve lost all these pieces of youth and community not out of intent, but necessity.

I believe this is the real reason we see so many young adults grapple with loneliness in their early to mid 20s: after school, so many of us find ourselves stripped of an easily accessible community. And afterwards, it can be hard not to lose ourselves in that newfound solitude.

This, of course, is a dilemma that affects us all, but what feels so different is men’s response to it.

The discourse surrounding the so-called “male loneliness epidemic” has long since hit a proverbial wall, and I think it’s due primarily to a collective satisfaction in assigning blame over finding its cause and solution.

And to do that, I want to attack the misnomer of male “loneliness” to begin with.

Men aren’t lonely, we’re scared of the vulnerability that comes with being known. To be known is to bear our souls to another, and invite the possibility of the pain and rejection that comes with it. It’s why we don’t like to open up to anyone, even our closest friends.

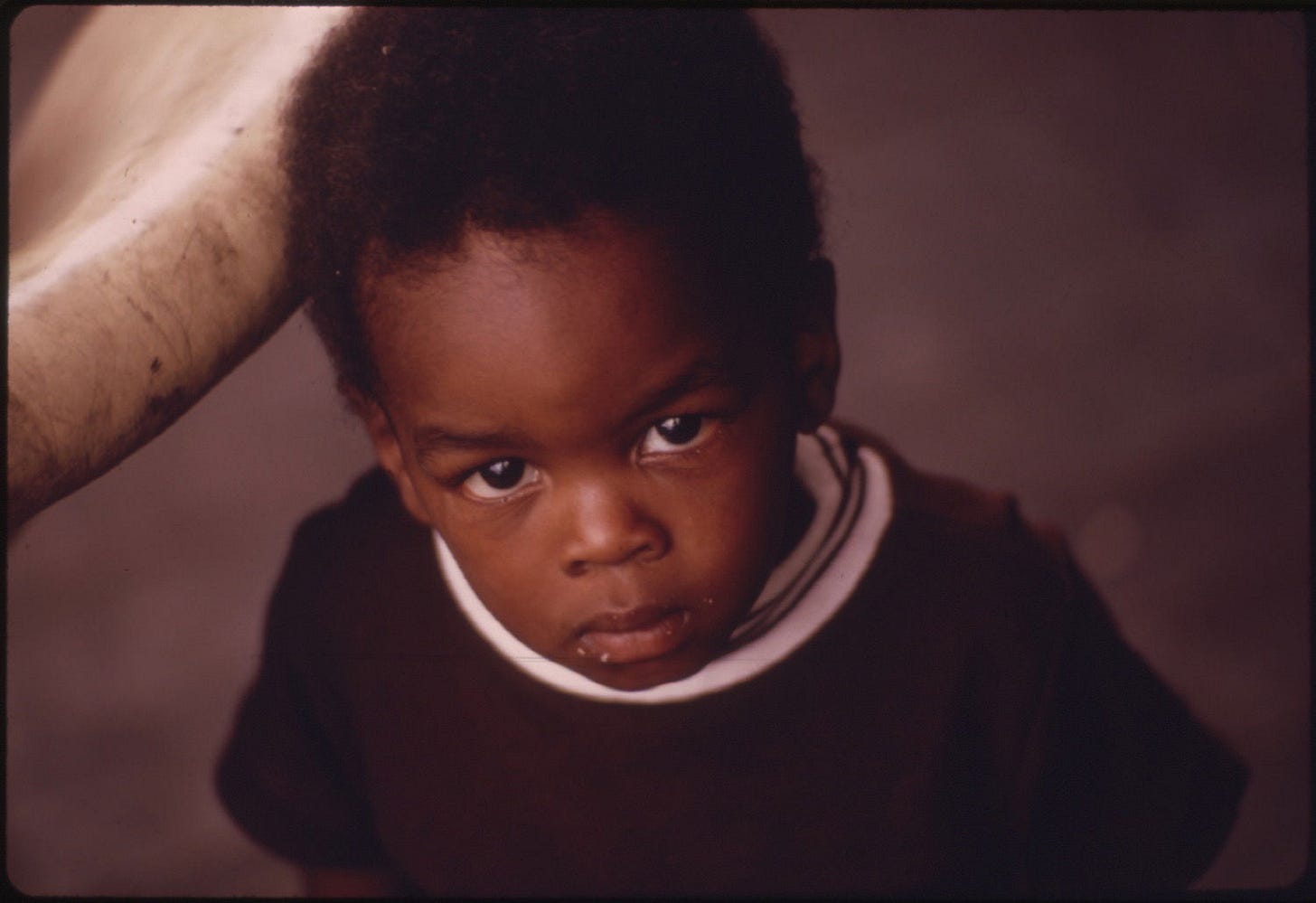

Boys are born into this world raised on two principles: That his emotions are signs of weakness and his worth is wholly material.

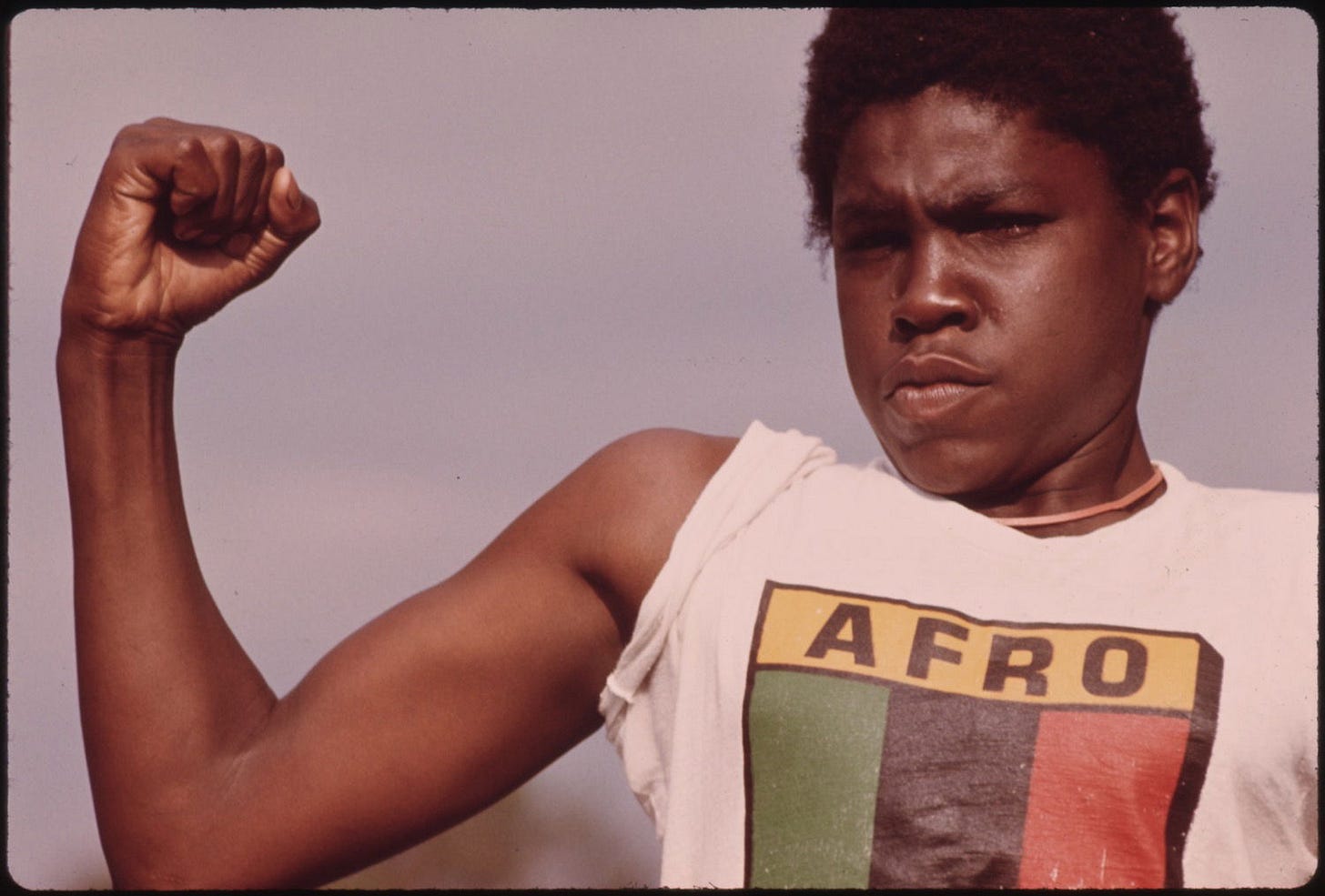

As a result, men have socialized ourselves to judge each other not on personal worth, but net worth. We seek not to be enriched, fully-fledged individuals, but “high-value men”.

Where women find personal development in the cultivation of multifaceted lives filled with fitness classes, scheduled lunches/dinners, nights out with friends, and time alone to care for themselves, men seek growth through “locking in” and “disappearing for 3 months”. We seek not to cultivate a world, but to build a single house on a barren hill and let it define us.

As a result, men have found ourselves in , stripped-down lives with a phantom pain for what could be, leaning on romantic and sexual relationships to not only build those worlds for us, but to provide the social fulfillment dozens of people would otherwise provide.

I believe Fight Club had a very strong point when it put forward the idea that “self-improvement is masturbation”, though I’m not sure it’s in the same vein that Tyler Durden intended.

Much of “self-improvement” media for men is an embellished, unrealistic depiction of what it means to improve your life. While it may sell the bones and visage of success, it’s a product before it’s anything else.

Much of “self-improvement” media for men involves this idea that to improve yourself and your life, you need to put all of your eggs in the basket of fitness, financial well-being, and intelligence. That in order to earn love and success, one has to EARN it.

In that sea of mental and physical labor, however, it’s easy to forget what we all live for: community.

We can attack our loneliness in the same way one would a weight loss goal or degree: with intentionality.

We can build worlds for ourselves out of the clubs we attend, the hobbies we cultivate, the art we consume, etc. The only hurdle along the path is just that: Doing it on purpose.

Naturally, there’s much more to tackling that hole in your heart than to simply “touch grass”, but as Occam’s Razor dictates: the simplest solution is oftentimes the best.

So go out and meet people, guys. Pick up a painting class. Start skateboarding. Join a run club. Build a life for yourself, and let thy cup runneth over.

Image Source: Image Public Domain